This Is My Biggest Website Mistake

It seems to me that the person writing a blog probably wants to talk about their greatest successes. Meanwhile the person reading it might prefer to read about the failures. In the years I have run this website, I have made many changes, and some of those changes have not been beneficial.

To restate, those changes were mistakes. Consider the era in 2015 when I decided to use JavaScript to try to improve the site. I would use async JavaScript to generate pages client-side. In 2015, JavaScript compilers were advancing quickly, and website owners wanted to benefit from this new technology.

Content websites should stick to static HTML, CSS and media files. When I moved to a JavaScript-heavy website layout:

So using JavaScript too much on a content site like this one was a clear failure. It consumed more time than I wanted, and it made things worse for all consumers of the site. I learned my lesson: for content-heavy sites, stick with static HTML and CSS along with media files (like WEBP).

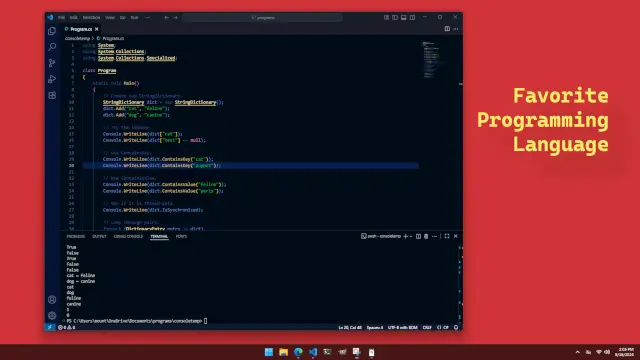

This Is My Favorite Programming Language

This site has articles focusing on more than ten different programming languages. Each one has its arrays, for-loops, function calls, and if-statements. But which programming language is my favorite? It is important to distinguish between my favorite, and which language I consider the best.

I feel that Rust is the best programming language of the ones I have written about. I don't feel any other language comes near the level of validation and performance that Rust offers. But my favorite? Rust can be a hassle to work with—it can make even an experienced developer feel insecure about their abilities.

I have to give the "favorite" award to the C# language. I feel C# is an efficient and fully-featured language that can be used to get real-world tasks done. It has good support in development environments, and copious amounts of documentation is available on the web (and with chat bots).

While in Rust I sometimes struggle to figure out what crate to use for a feature, in C# knowing where a feature is located is often obvious—and included in the standard library. For example, Rust uses an external crate for random numbers, but in C# you use System.Random. Learning the C# standard library is worthwhile, as it can handle a large percentage of the programming tasks you might face in the future.

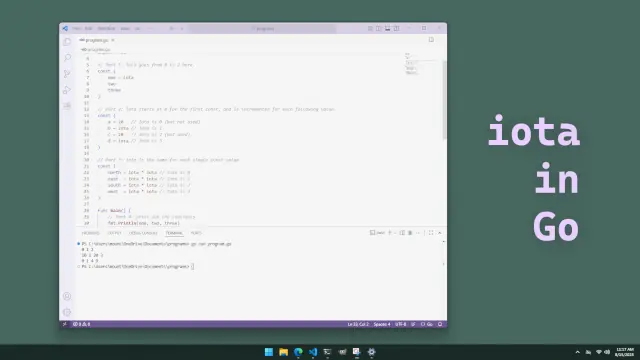

Is Iota in Go Worth Having

When I was first learning Go, I was interested most in the features it had that other languages did not. For example, it has a special keyword called iota. Now Iota is the letter "I" in the Greek alphabet. But in Go it is an incremented value in a const block.

At best, iota is a small convenience so that developers do not need to type out 0, 1, 2, and further numbers. But that is all it is good for. It does not provide any useful functionality that cannot be duplicated easily just by using some integers.

I suppose iota could:

In the Go programs I have written, I don't think I have ever bothered with iota. Basically getting a running and correct program has always been more important than using a shortcut for a number sequence. My end conclusion is that iota probably does not add much value, and having a simpler language might be better than having iota.

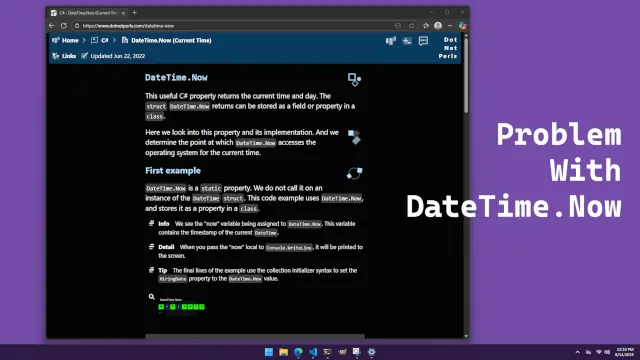

Problem With DateTime.Now in C#

In C# the idea of properties is that they are externally-visible getter and setter methods that are fast to access and have no external effects. For example, the Length property on a string can be accessed, it is a simple memory load, and it won't change out from under you.

This brings us to DateTime.Now, a commonly-used property in C# on the DateTime struct. In my testing, DateTime.Now is many times slower than a memory load—this depends on the system, but it makes an OS call to get the current time. According to the rules of properties, DateTime.Now (and Today) should not even be properties.

I guess this brings us to the problem of properties in C#. Properties annoy me because:

Another thing about properties and performance: what about a lazily-initialized field on a class? Should this be a property if it is slow to access for the first time, but fast on all following accesses? Technically, it should not be, as it is not like Length on a string. And for the same reason DateTime.Now should have been a method called DateTime.GetNow.

Google Search Is a Legacy Product

Some months ago I stopped using Google Search. I had noticed the quality of the results were terrible, and there were ads and shopping sections everywhere. It would rewrite my queries so that they were more profitable to Google. It was no longer useful to me, so I moved on to other things.

With the introduction of ChatGPT, LLMs became an option to answer queries about the world. But eventually I figured out that LLMs can be run locally, and when you do this, you can keep all your queries local to your own computer. No external website gets any information about a local LLM query.

Both Google and OpenAI (along with many other companies) release open-weights LLMs like Gemma and GPT-OSS. These can be run on relatively new computers with consumer-grade GPUs. When run, these LLMs do not insert shopping links and ads everywhere—they do not rewrite my query with the intent to sell me stuff.

For current events and weather, a search engine is still useful, but I have found Bing is approximately as good as Google on most queries, and for the ones where there is a quality difference, Bing is the one that tends to be superior. I guess tech products do not last forever—consider Yahoo Search and Facebook. Google Search is a legacy product—one so weighted down by its past successes, and its owner's constant need for revenue, that it has become unusable now.

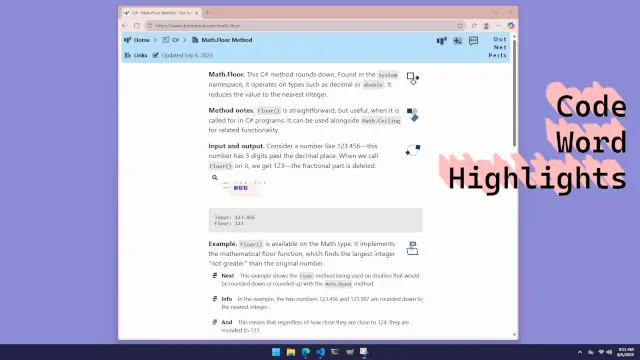

Code Word Highlights

Nearly every developer uses syntax highlighting for viewing code. It helps to have keywords and function names highlighted in different colors. However, even when writing about code (in paragraphs of text), it helps to have code words be highlighted somehow.

For example, suppose you are writing about Dictionary, a specific class in C#. But a person might not know this and think you are writing about a dictionary, like a way to check definitions of words. So it helps to highlight the code term Dictionary if that is the subject.

I put some time into adding code word highlighting on the site. It works by:

HashMap (or Dictionary if you prefer) of terms.I think the new approach makes the site easier to read and use. It can be overwhelming on pages with too many highlights, but overall I find it an improvement.

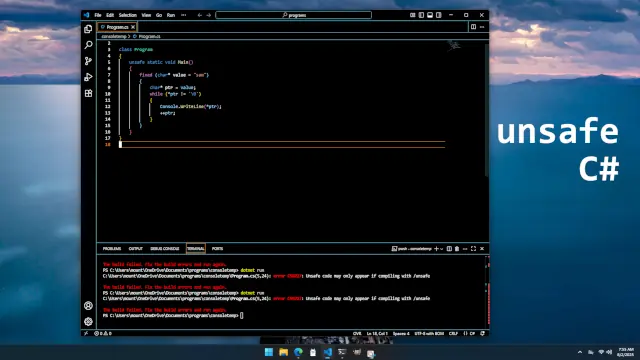

Unsafe Code in C#

C# is a well-optimized language—the most commonly used implementation is at least. But suppose this is not enough for you. For your important project you want to be able to manipulate pointers and raw memory directly. In this case you can use unsafe code blocks.

Keywords like fixed and stackalloc can make programs that were once easy to understand, very hard to understand. But does using these unsafe optimizations even work—does it make programs faster? It does, but only in specific, well-tested situations. For example the GetHashCode method on string has been implemented with unsafe code.

In actual programs, that use strings and for-loops, unsafe code is of dubious benefit. In fact, I have found:

unsafe code typically makes programs slower, due to the cost of pinning memory (which stops the garbage collector).To be blunt, I am not a fan of unsafe code blocks in C#. In Rust, unsafe refers to code that hasn't been proven safe, but in C# unsafe just refers to code that manipulates raw memory with pointers. Probably the first thing to do if a C# project uses unsafe code is to remove or rewrite the code to standard C#.

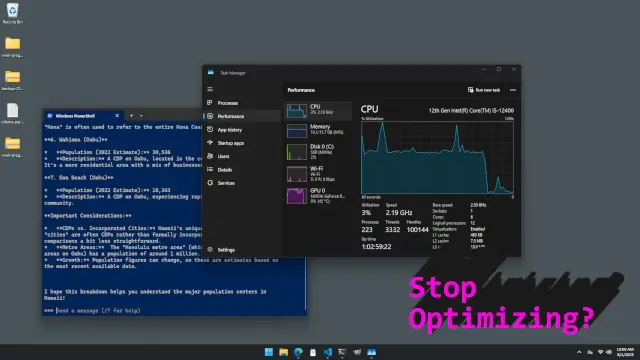

When to Stop Optimizing a Program

Suppose you make a cool and useful program that does something you are interested in. And with time, you add more data and the program runs slower and slower. Some optimization work is necessary, but this can be taken too far—when do you stop optimizing the program? When is fast, fast enough?

The simple answer is: I don't know. You should probably just read someone else's blog if you want to know the answer. There are a lot of considerations here—if you enjoy optimizing computer code, you probably should spend more time doing this activity. And if the program is more of a hobby instead of work, it may also warrant more attention.

Even for enthusiasts, though, there needs to be a limit. Optimization can lead to negative outcomes such as:

Sometimes it can be a better idea to change the design of the program so that it does not need as much optimization—usually by making it simpler. However, a certain amount of optimization is helpful to nearly any program. Computers are supposed to automate our work, and as everyone knows, there is nearly an infinite amount of work to do—so it best be done quickly.

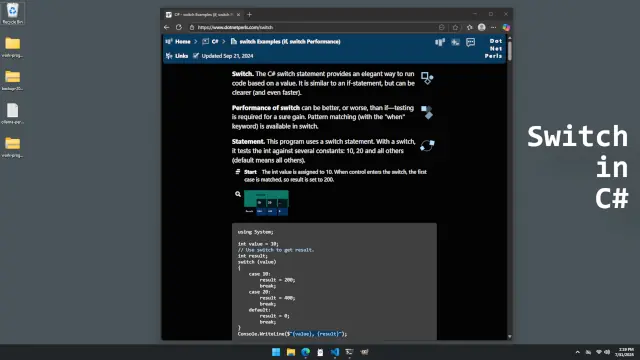

When to Use Switch in C#

It is said that the decisions we make determine the lives we live. For developers, we must determine whether to use an if-statement or switch. Should developers use switch more often? And if so, when should switch be preferred—should we always replace if-chains with switch blocks?

Let's consider an if-else chain that tests for numbers. If all the cases are constant, we can convert the if-block into a switch statement. In newer versions of C# we can use ranges and expressions in switch statements—so even more if-chains can be converted.

There are some benefits that can be realized by using switch. The switch statement:

if-else chain, but this probably will only happen in situations with constant integer cases.if-statement if one case occurs frequently, and an if-statement check for it first.If I am handling a set of char values, like lowercase letters or punctuation I would prefer a switch. My thinking is that if there is a complete set of cases we want to consider, and they are all mostly equal in importance, and the cases are simple values like char or int, prefer a switch. Otherwise, reach for the old standby if-statement.

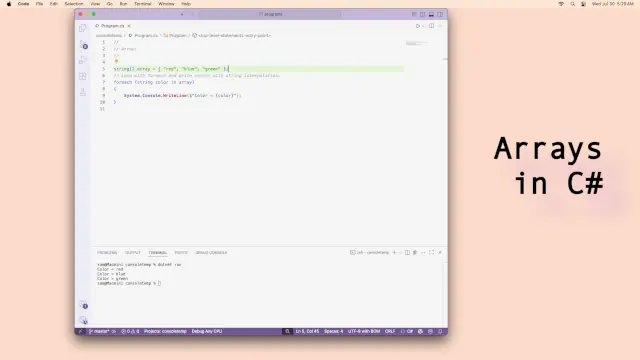

When to Use Arrays in C#

Probably my favorite class in C# is the List. It expands to hold as many items as you want, and it can be set (through the generics syntax) to hold any element type you desire. But arrays in C# offer some clear benefits, too—though they are less often needed.

An array is different from a List mainly because it cannot resize its buffer on its own. An array of 100 elements will always have 100 elements (though elements could be null). For this reason, we should prefer arrays only when we know the exact element count beforehand—like for a buffer of bytes we read data into.

Arrays are preferred only when:

Basically, if your program's goal is to read strings from a file, you will want a List. But if you want to store 10 strings in a class for later use, a string array is a better choice. Usually the List is the better first choice.